What Is High-Functioning Depression?

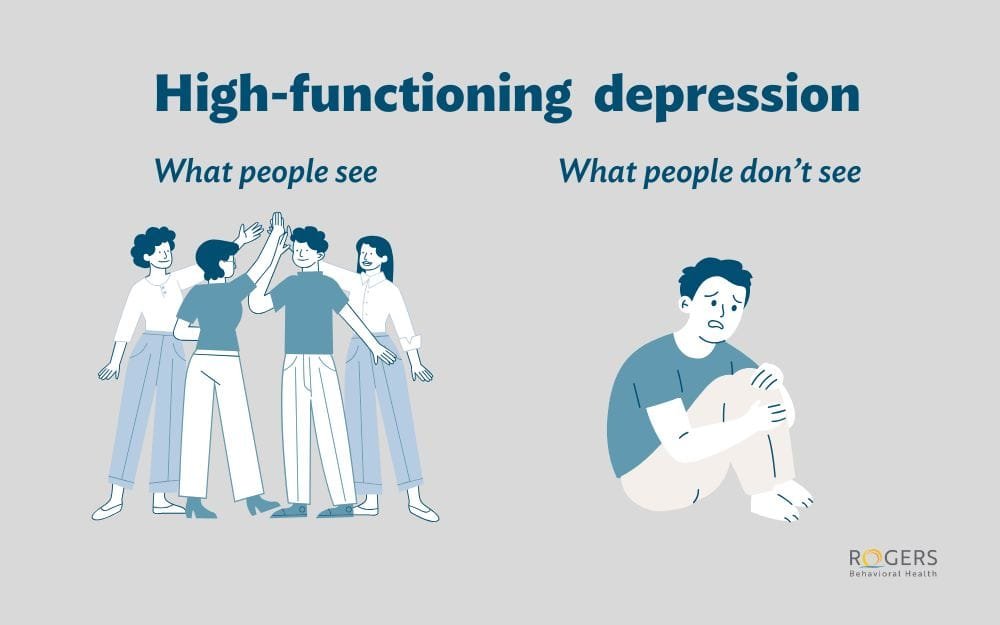

High-functioning depression is not an official diagnosis in manuals like the DSM-5, but it’s a commonly used term to describe people who live with depressive symptoms over long periods while still maintaining daily responsibilities: work, family, social life. They might “look fine” from the outside — showing up to work, fulfilling roles, keeping routines — but underneath there can be chronic low mood, self-criticism, fatigue, and emotional numbness.

Clinically, high-functioning depression often overlaps with Persistent Depressive Disorder (PDD), also known as dysthymia — a long-term, less-severe form of depression where symptoms persist for at least two years in adults.

How It Shows Up, Especially in Men

Because of gender norms and social expectations, high-functioning depression in men often looks different (and is more easily hidden) than more classic depressive episodes.

Some patterns:

Masking with productivity: Overworking, hyper-focus on tasks, perfectionism — accomplishments may temporarily distract from the internal struggle.

Irritability or anger rather than sadness: Men may act out more than they cry out. Emotional regulation becomes frustration or low threshold for annoyance.

Self-criticism & low self-esteem: Even when externally successful, there’s often a constant internal voice of inadequacy or fear of failing.

Physical symptoms: Fatigue, sleep difficulties (insomnia or poor sleep), low energy, maybe appetite changes. These might be blamed on “being busy” rather than recognized as part of mood disorder.

Withdrawal & isolation: While keeping up with responsibilities, men may quietly pull away from hobbies, friends, and emotional connection. Social contact becomes superficial.

Avoidance of help: “I’ll deal with it myself,” “It's not that bad,” or “If I can still do my job/family obligations, I must be okay.” These beliefs delay help.

These patterns often go unrecognized by others — family may assume everything is fine, colleagues may see someone who pushes through, and men themselves may believe the depression is just stress, tiredness, or part of personality.

How Common Is It in Australia?

Data specific to high-functioning depression is limited (since it isn’t officially defined in many diagnostic systems), but broader studies on depression suggest the conditions for it are quite widespread.

Some relevant stats:

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing 2020-2022 found that 21.5% of people aged 16–85 had a mental disorder in the past 12 months. Anxiety disorders were the most common; many people with mental disorders do not access professional help.

The “Ten to Men” study (AIFS) showed that for many men, mild or moderate symptoms of depression (not necessarily meeting “major depression”) are common. Many report symptoms like low energy, trouble sleeping, being tired, or loss of interest—symptoms consistent with high-functioning depression.

Persistent depressive symptoms over time, even if fairly mild, are linked with poorer quality of life, relationship issues, and higher risk of escalation to more severe depression. Longitudinal studies show that depression trajectories (how symptoms change over time) vary, but many individuals with milder chronic symptoms have worse long-term outcomes than they expect.

So while precise prevalence numbers for “high-functioning depression” are hard to nail down, the conditions for it (chronic, mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms, unmet help, functional but suffering) are definitely widespread among Australian men.

Why It’s So Hard to Spot and Why It’s Dangerous

Because men with high-functioning depression still hold things together outwardly, it often slips under the radar — by themselves, by friends/family, and by health professionals. Here are some of the reasons and risks:

Cultural stigma: Many men believe admitting emotional pain is a weakness. They might be comfortable talking about physical pain, but not mental. Fear of being judged or “losing face” is powerful.

Misattributing symptoms: Fatigue, irritability, poor sleep — these are often attributed to stress, workload, lifestyle. Men (and clinicians) may treat them as separate issues, not part of depression.

Sustained stress & burnout: Keeping up outward responsibilities uses emotional energy. When there’s no outlet or support, emotional reserves drain, increasing risk of burnout, panic, or more severe depressive episodes.

Relationship harm: Intimacy suffers. Communication degrades. Partners may feel distanced or misunderstood when a man seems “fine” but is emotionally distant.

Risk of escalation: Milder symptoms may escalate into more severe depression or even suicidal ideation if left untreated. For example, in the ABS data, a significant portion of people with mental disorders do not seek help — and untreated disorders tend to worsen.

What Helps: Treatment & Coping Strategies

Recovering or managing high-functioning depression is absolutely possible. Here are approaches shown to help, especially in the Australian context:

1. Professional therapy/counselling

CBT (Cognitive Behavioural Therapy) is one of the best-evidenced therapies for depression and anxiety. Helps in restructuring negative thoughts, behaviours, and patterns.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and other mindfulness-based therapies can help reduce self-criticism and foster acceptance.

Finding a therapist who understands male mental health dynamics (e.g., pressure to “keep going,” performance, identity) helps.

2. Lifestyle interventions

Regular physical activity: even moderate exercise improves mood, reduces anxiety, increases energy.

Sleep hygiene: consistent sleep time, reducing screen usage before bed, improving sleep environment.

Nutrition: balanced diet, avoiding over-reliance on stimulants, alcohol.

3. Social connection and vulnerability

Sharing with trusted friends/family what’s really going on. Even if it’s small.

Peer support groups: men can feel more validated when hearing others’ stories.

4. Mindfulness, stress reduction and self-awareness

Mindful meditation, breathing work, journaling to catch negative thoughts.

Setting boundaries at work or home; making space for rest.

5. Medical/Medication support

Sometimes antidepressants or other psychiatric medication are needed — particularly if symptoms intensify or persist.

Regular check-ups with GP or psychiatrists.

6. Early intervention and monitoring

Recognising signs early before burnout or more severe depression.

Using self-assessment tools (PHQ-9, etc.) to track mood.

Being proactive: don’t wait for a crisis.

What Men (and Their Supporters) Can Do

Here are practical steps, grounded in research and real experience:

Start small: First step might just be admitting to yourself: “I’m not okay inside, even though on the outside I seem fine.”

Seek trusted spaces: A friend, counsellor, or group where vulnerability isn’t shamed.

Build rituals of self-care: Even small routines (morning walk, regular bedtimes, journaling) can help stabilise mood.

Language matters: Changing how we talk about depression — moving away from labels like “crazy,” “weak,” to “struggling,” “needing rest,” “mental health” helps reduce shame.

Use available Australian supports:

MensLine Australia — 1300 78 99 78

Free, confidential counselling helpline for men.

Beyond Blue — 1300 22 46 36

Resources and support across the spectrum of depression and anxiety.

Lifeline — 13 11 14

Immediate crisis support.

GPs — don’t underestimate the power of regular medical check-ins (physical health can influence mental health).

Real Stories & Lived Experience (Why It Matters)

Many men report that others don’t notice what’s going on inside them because they keep “doing the things” externally — work, home, family. They say things like “if I didn’t wake up and go to work, people would notice.”

Some say their depression feels like a constant background noise — always present but ignored. Because it’s “always there,” it becomes their baseline, which can make it feel like there's no other option.

These lived experiences show how urgent it is to bring awareness to high-functioning depression — so people know it exists, symptoms are validated, and help is more accessible.

Conclusion

High-functioning depression is one of the most insidious mental health challenges. It can hide behind smiles, productivity, and “I’m fine” responses. Yet the emotional toll is real — on self, on relationships, on long-term wellbeing.

For Australian men, the added layers of masculinity norms, stigma, and the tendency to suppress emotional pain make it even more challenging. But there’s hope.

By naming high-functioning depression, talking about it openly, and combining professional help with self-care and connection, men can reclaim emotional health and live lives that are more than just coping — but flourishing.

If you resonate with this, remember: you’re not alone. Reaching out doesn’t make you weak — it makes you courageous. Healing is possible.